Introduction

In modern economies, income and sales taxes have become the primary methods through which governments collect revenue. However, both forms of taxation suffer from inherent limitations that undermine their effectiveness in supporting the fiscal needs of a sovereign government. Income taxes, while progressive in theory, are riddled with loopholes that favor the wealthy, leading to widespread tax avoidance and a regressive impact on the middle class. The complexity of the income tax system imposes an administrative burden that wastes both taxpayer and governmental resources, resulting in inefficiency and public resentment.

Sales taxes, on the other hand, create a regressive burden on lower-income households, who must spend a higher percentage of their income on necessities. This type of taxation exacerbates inequality and distorts consumer behavior, while also being subject to volatility during economic downturns. Despite their ubiquity, sales taxes disproportionately impact those who can least afford them, leading to an unfair distribution of the tax burden.

Both income and sales taxes are also inherently cyclical. As economic activity slows during recessions, so do tax revenues, precisely when governments need to spend more to support recovery. This forces governments to either cut spending or borrow more, further exacerbating deficits and placing a long-term strain on public finances.

Given these significant flaws, relying on income and sales taxes to fund sovereign governments not only perpetuates inequality and inefficiency but also makes governments vulnerable to the cyclical nature of economic activity. While alternative approaches to taxation have been explored, such as wealth taxes, these also face similar administrative and compliance challenges. The need for a more sustainable and equitable approach to government financing is becoming increasingly apparent.

This chapter will explore the inherent shortcomings of income and sales taxes, examining their economic impact, fairness, and role in perpetuating structural imbalances. By understanding these limitations, we can pave the way for a more effective and just approach to public finance in the future.

Income Taxes

Administrative Burden

Income taxes, while essential to modern fiscal systems, come with a significant administrative burden that undermines their efficiency. The complexity of the tax code requires an enormous bureaucracy to manage, enforce, and audit. Taxpayers, both individual and corporate, face a system laden with deductions, credits, exemptions, and varying rates, which necessitates extensive record-keeping and compliance efforts.

The U.S. tax code, including income taxes, is often cited as being approximately 70,000 pages long when including all related regulations, rulings, and additional guidance, though the actual Internal Revenue Code (IRC) itself is around 2,600 pages. The larger figure includes related federal tax regulations, case law, and other administrative materials

The IRS must dedicate substantial resources to overseeing tax compliance. This involves processing millions of tax returns, conducting audits, and investigating tax avoidance schemes. The sheer scope of this work leads to inefficiencies, as the agency struggles to keep up with an ever-evolving tax code and the creative ways in which taxpayers, particularly wealthy individuals and corporations, exploit loopholes.

For taxpayers, this complexity results in considerable costs. Many individuals and businesses are forced to hire accountants, tax preparers, or legal experts to navigate the intricacies of tax law. This adds a layer of inefficiency, where compliance costs consume a portion of both private and public resources that could otherwise be directed toward productive economic activity.

Moreover, the administrative burden fosters inequality. High-income individuals and large corporations, with access to sophisticated legal and financial advice, can exploit tax avoidance strategies that reduce their effective tax rates. Meanwhile, middle- and lower-income taxpayers often lack the resources to take full advantage of available deductions, bearing a disproportionate share of the tax burden. This further exacerbates income inequality while making enforcement more challenging for tax authorities.

Finally, the complexity of the system opens the door for widespread tax evasion. With tax authorities stretched thin, individuals and businesses can underreport income or exaggerate deductions with relatively low chances of being caught. This not only reduces government revenue but also undermines public trust in the tax system.

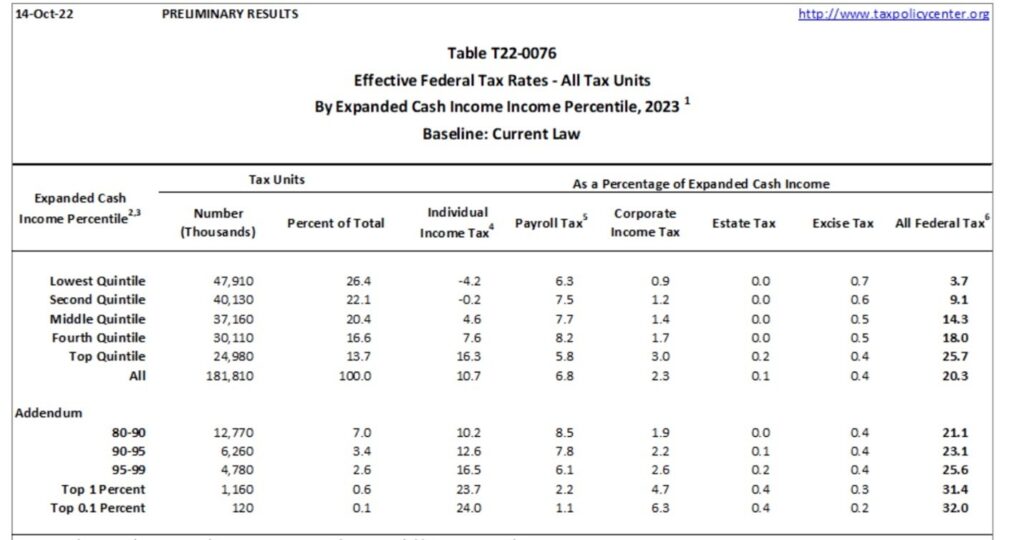

Source: https://taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/baseline-average-effective-tax-rates-october-2022/t22-0076-average-effective-federal This table shows what individuals and corporations actually paid in taxes, not their tax rates. Especially notable is the effective corporate tax rate on income, which is 6.3% while the tax rate is 21% on all income starting at dollar 1.

In sum, the reliance on income taxes imposes heavy administrative costs on both the government and taxpayers, creates inequities in enforcement, and allows tax avoidance and evasion to flourish. These inefficiencies highlight the inadequacy of income taxes as a reliable and fair source of government revenue.

Tax Evasion and Avoidance

Tax evasion and avoidance are significant byproducts of the complex income tax system, leading to both revenue losses and deepening inequality. These practices are widespread, particularly among high-income individuals and corporations, and create a system in which the tax burden is disproportionately shifted to those who cannot afford or access similar strategies.

Tax Gap

The most direct consequence of tax evasion and avoidance is the impact on government revenue. The IRS regularly estimates a substantial tax gap, the difference between what taxpayers owe and what is actually collected. This gap is driven by underreporting of income, exaggerated deductions, or simply not filing taxes at all. Conservative estimates suggest that the U.S. loses hundreds of billions of dollars annually to this gap, with a significant portion attributable to higher-income individuals and corporations who have the means to exploit loopholes.

This lost revenue forces the government to either increase taxes on those who are already paying or cut back on essential services and programs. The result is a heavier burden on middle- and lower-income earners, who tend to comply more fully with the tax code due to a lack of resources or opportunities to engage in more sophisticated tax strategies.

Offshore Tax Havens and International Schemes

At the corporate and high-income individual level, offshore tax havens play a critical role in avoiding U.S. taxes. By shifting profits or assets to low-tax or no-tax jurisdictions, multinational corporations and wealthy individuals can effectively bypass the U.S. tax system. This practice, while technically legal in many cases, raises ethical concerns and leaves U.S. authorities struggling to recapture lost revenue.

Efforts like the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative have made strides in addressing these practices on a global scale, but enforcement remains a challenge. The ability to move wealth across borders adds another layer of complexity to the already burdened IRS, further illustrating the inefficiencies of relying heavily on income tax.

Inequality and Unfair Advantages

Tax avoidance is primarily a luxury for the wealthy. High-income earners and large corporations can afford the best tax advisors, lawyers, and accountants to find loopholes, set up offshore trusts, and implement strategies that reduce their tax liabilities. In contrast, middle- and lower-income taxpayers do not have the same access to such resources, forcing them to pay higher effective rates.

This dynamic worsens inequality. Wealthy individuals can shield significant portions of their income, while regular taxpayers shoulder a greater share of the nation’s tax burden. In this sense, income tax avoidance and evasion are not just financial issues; they are societal problems that deepen existing divisions and foster resentment.

By allowing such widespread tax evasion and avoidance, the income tax system not only loses significant revenue but also creates an environment where those with the greatest ability to pay contribute the least. These practices further demonstrate the inadequacies of income tax as a central method of funding government functions.

Disincentive to Work and Invest

Income taxes, particularly at higher marginal rates, can create a disincentive for individuals to work more or invest in their businesses. When people realize that additional earnings will be heavily taxed, their incentive to put in extra hours or take on additional work diminishes. This effect is especially noticeable among high-income earners, who face higher marginal tax rates as they climb income brackets. The result is a reduction in overall productivity, as the potential reward for extra effort does not align with the amount of work required to achieve it.

For businesses and entrepreneurs, income taxes also serve as a deterrent to investment. When businesses are taxed heavily on profits, there is less motivation to reinvest those profits into expansion, hiring, or innovation. Entrepreneurs, particularly those running small businesses, may decide that the risks associated with investing their time and capital are not worth the potential after-tax returns. This hesitancy reduces the dynamism of the economy, limiting job creation, innovation, and economic growth.

Moreover, higher income tax rates can lead to changes in behavior that slow economic development. For instance, individuals and corporations may prioritize tax avoidance strategies over productive activities, diverting resources away from job creation and investment into finding ways to minimize tax liabilities. This behavior not only reduces tax revenue but also distorts the economy, as resources are allocated based on tax considerations rather than economic efficiency.

In the long run, a system that relies too heavily on income taxes to fund the government risks stifling the very economic activity that generates wealth. By discouraging work and investment, high income taxes undermine the growth potential of the economy, ultimately limiting the government’s ability to raise revenue and support public services.

Inequality Amplification

Income taxes, despite their progressive structure, often exacerbate inequality rather than reduce it. While tax brackets are designed to impose higher rates on those with greater income, the reality is that the wealthiest individuals and corporations have access to tools and strategies that allow them to avoid or minimize their tax liabilities. This results in an unfair system where the wealthy, who have the greatest ability to contribute, end up paying proportionally less than middle- and lower-income individuals.

One of the key mechanisms through which income taxes amplify inequality is the disparity in how different types of income are taxed. For example, capital gains and dividends, major sources of income for the wealthy, are often taxed at lower rates than ordinary wages. This means that wealthy individuals, who derive much of their income from investments, face a lighter tax burden than those who earn a paycheck. The gap between these tax rates further widens the wealth divide, as ordinary workers are taxed at higher rates on their labor while wealth accumulates more favorably in the hands of investors.

Additionally, the use of deductions, credits, and loopholes provides the wealthy with even more opportunities to reduce their tax obligations. High-income earners can afford teams of accountants and lawyers to exploit these provisions, minimizing their effective tax rates. Meanwhile, middle- and lower-income individuals, who lack access to such resources, bear a disproportionate share of the tax burden. As a result, income taxes do little to counteract the structural forces that contribute to inequality.

Over time, this unequal tax burden contributes to the concentration of wealth. As the rich get richer, they are able to invest more, further compounding their wealth through favorable tax treatment of investment income. In contrast, lower-income individuals find it harder to build wealth because a larger portion of their earnings is consumed by taxes, leaving less for savings or investment. This cycle perpetuates and deepens the inequality that progressive income taxes were, in theory, supposed to address.

Ultimately, income taxes not only fail to reduce inequality but often amplify it, creating an economic environment where wealth becomes more concentrated at the top. This unequal distribution of the tax burden undermines the broader goals of fairness and social cohesion, reinforcing the need for a more equitable system of public finance.

Cyclicity

One of the most significant flaws in relying on income taxes as a primary source of government revenue is their inherent cyclicality. Income taxes are closely tied to economic activity, which means that tax revenues rise during periods of economic growth and fall during recessions. This cyclical nature makes income taxes a volatile and unreliable source of funding, particularly when government spending needs are highest, during economic downturns.

In times of economic growth, tax receipts swell as employment rises, wages increase, and businesses see higher profits. While this may seem advantageous, the problem arises when the economy enters a recession. As unemployment rises and wages stagnate or fall, individual tax revenues decline. Simultaneously, corporate profits shrink, leading to a steep drop in business tax receipts. This creates a paradox: the government collects less revenue precisely when it needs more to stabilize the economy, provide public services, and stimulate growth.

This cyclicality exacerbates fiscal challenges because government spending often increases during recessions. Unemployment benefits, social services, and economic stimulus measures are critical during downturns but must be funded when tax revenues are falling. As a result, governments are forced to borrow heavily or cut essential services to make up the shortfall. This reliance on borrowing increases public debt, creating long-term fiscal burdens that can destabilize economies and constrain future government spending.

Furthermore, the volatility of income tax revenues complicates government budgeting. It becomes difficult to predict revenues year after year, leading to underfunded programs or overly conservative spending projections during downturns. In boom periods, surpluses may lead to short-term increases in spending, but these are unsustainable when the economy contracts. This boom-and-bust pattern in public finances can lead to inefficient government planning and the misallocation of resources.

In short, the cyclicality of income taxes makes them an unreliable and unstable source of revenue for a sovereign government. Their tendency to decline during economic downturns forces governments to either borrow more or cut critical services, exacerbating fiscal imbalances. For a more stable and effective financial system, alternative methods of funding government functions are necessary, ones that are less dependent on the unpredictable swings of the business cycle.

Sales Taxes

Regressive Nature

Sales taxes, by their very design, disproportionately impact lower-income individuals, making them inherently regressive. Unlike income taxes, which are typically structured to tax higher earners at higher rates, sales taxes apply the same rate to all consumers, regardless of their income level. This means that lower-income individuals, who must spend a larger portion of their earnings on necessities, end up paying a much higher percentage of their income in sales taxes compared to wealthier individuals.

For low-income households, a significant portion of their earnings is spent on essential goods and services such as food, clothing, and transportation. Even in cases where certain essential items are exempt from sales taxes, the overall burden of consumption taxes falls heavily on these households. In contrast, wealthier individuals can save or invest a larger share of their income, meaning that a smaller percentage is subject to sales taxes.

This regressive nature amplifies inequality. As lower-income individuals are forced to dedicate more of their income to meeting basic needs, they are left with less disposable income for savings or investments. This creates a cycle in which the wealth gap widens over time. The wealthy, by comparison, enjoy a relatively lower tax burden from sales taxes and can accumulate and grow their wealth with fewer tax obligations.

In summary, the regressive structure of sales taxes unfairly shifts the tax burden onto lower-income households, deepening inequality and leaving many individuals with less financial flexibility. As a means of generating government revenue, sales taxes may seem simple, but their disproportionate impact on the poor makes them an unjust and inadequate solution for funding a sovereign government.

The Narrow Tax Base

One of the critical limitations of sales taxes is their narrow tax base, meaning that a large portion of goods and services remains untaxed. Sales taxes were originally designed to tax tangible goods, which made sense when the economy was largely based on manufacturing and physical products. However, as the economy has shifted toward services and digital products, sales taxes have failed to keep pace.

Today, services account for approximately 70% of personal consumption, but most of these transactions are not subject to sales tax in most states. Only a few states, such as Delaware, Hawaii, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Washington, broadly tax services, while most other states limit their sales tax to a specific set of services like telecommunications, utilities, or repairs. The limited taxation of services leaves a significant portion of the economy untouched by sales tax, reducing the effectiveness of this revenue stream.

Moreover, states often exempt essential goods like groceries and prescription drugs to minimize the regressive impact of sales taxes on low-income households. While these exemptions are well-intentioned, they further erode the sales tax base, making the system even narrower and more reliant on taxing discretionary spending.

As the economy continues to evolve, more goods are being replaced by digital services, such as streaming or downloadable content. While states have begun to address this shift, roughly half still do not tax digital goods or services.

This gap in taxation creates distortions in the market, as businesses offering digital products gain a competitive advantage over those selling physical goods that are subject to sales tax. It also means states are missing out on significant potential revenue from the growing digital economy.

The narrow tax base forces states to impose higher sales tax rates on the items that remain taxable, further exacerbating the regressiveness of the tax. As fewer goods and services are taxed, the tax burden on everyday consumers increases, especially on discretionary items like clothing, electronics, and other non-essential purchases. This limited base and the rising rates make the tax less efficient and more prone to economic distortions.

In summary, the narrow tax base of sales taxes, exacerbated by the exclusion of many services, digital goods, and essential items, limits its effectiveness as a reliable revenue source. As the economy continues to shift away from tangible goods, states that rely heavily on sales taxes are likely to experience increasing revenue shortfalls, further highlighting the inadequacy of this tax as a long-term solution for funding government functions.

Inflationary Pressure

Sales taxes directly contribute to inflation by increasing the final cost of goods and services. When a sales tax is applied to a product, the consumer pays more than the base price, which, in turn, reduces their purchasing power. This effect is particularly problematic in sectors where margins are already thin, as businesses often pass these taxes along to consumers, effectively making everyday items more expensive.

The inflationary impact of sales taxes is most noticeable in essential goods. Although many states exempt necessities like groceries or medicines from sales tax, other essentials such as clothing, transportation, or utilities are often taxed. As sales taxes increase the cost of these necessities, lower-income households, which spend a higher proportion of their income on basic goods, are disproportionately affected. This can lead to further economic strain as the cost of living rises faster than wages, reducing the real value of income, particularly for those with fewer resources.

Additionally, sales taxes are typically applied at aflat rate. This means that as prices rise due to inflation, the amount of tax collected on each purchase also increases, compounding inflationary pressure. For example, if the price of a good rises due to external factors (such as supply chain disruptions), the sales tax applied to that higher price further inflates the cost to consumers. This compounding effect worsens inflation, especially in times of economic instability or when external factors like fuel prices or import costs are already driving prices higher.

Moreover, businesses may factor sales taxes into their pricing strategies, passing the tax burden onto consumers by raising prices to maintain profit margins. This is particularly prevalent in competitive industries where businesses operate with tight margins and are unable to absorb additional costs. The result is a price increase across the board, which can create a ripple effect through the economy, further driving inflationary trends.

In summary, sales taxes amplify inflationary pressures by increasing the cost of goods and services, eroding consumers’ purchasing power, and contributing to a cycle of rising prices. These taxes not only make essentials more expensive for everyone, but they also disproportionately impact lower-income households, exacerbating the challenges of inflation in the broader economy.

Distortion of Consumer Behavior

Sales taxes create distortions in consumer behavior by influencing purchasing decisions in ways that would not occur in a tax-free market. When taxes are applied to goods and services, consumers often adjust their spending habits to minimize their tax liability, leading to choices that may not align with their actual preferences or needs. These distortions manifest in several key ways:

When sales taxes increase the price of certain goods, consumers may substitute these taxed items with untaxed or lower-taxed alternatives, even if the alternatives are not their first choice. For instance, if a state taxes restaurant meals but not groceries, consumers might opt to eat at home more frequently, not because they prefer it, but to avoid paying the tax. This substitution distorts the natural demand for goods and services and can have a negative impact on industries disproportionately affected by the tax.

In regions where states or municipalities have different sales tax rates, consumers may travel to nearby areas with lower or no sales tax to make their purchases. This behavior is common in border regions where tax rate disparities are significant, such as between states that do not impose sales taxes (like Delaware) and those that do. The result is a loss of revenue for higher-tax jurisdictions and an inefficient allocation of resources as consumers and businesses alter their behavior to avoid taxes.

Sales taxes can also lead consumers to delay or avoid certain purchases altogether, particularly for large-ticket items. For example, during sales tax holidays, consumers might time their purchases of electronics, clothing, or school supplies to coincide with the tax-free period, distorting regular spending patterns. While these holidays are meant to boost economic activity, they often just shift the timing of purchases rather than increasing overall consumption.

Businesses may respond to sales taxes by creatively bundling goods with non-taxable services or by attributing more of the cost to non-taxable components. For instance, a business might package a physical good with a non-taxable service to reduce the overall sales tax liability. This practice distorts pricing strategies and creates inefficiencies, as businesses focus on minimizing taxes rather than optimizing for market demand or consumer preferences.

High sales taxes, especially on goods like tobacco, alcohol, or luxury items, can lead to the growth of a black market where goods are sold without tax. Consumers seeking to avoid high taxes may turn to illegal markets, undermining legitimate businesses and depriving governments of revenue. This distortion erodes trust in the tax system and encourages non-compliance.

In conclusion, sales taxes alter consumer behavior in ways that lead to inefficiencies and economic distortions. By encouraging consumers to change their spending habits to avoid taxes, these distortions impact both demand for goods and services and the overall effectiveness of sales taxes as a revenue tool. The result is a less efficient economy, where market forces are skewed by the presence of taxation rather than driven by consumer preferences and needs.

Economic Inefficiencies

Reduced Disposable Income

Both income and sales taxes reduce disposable income, but they do so in different ways, each leading to its own set of economic inefficiencies.

Income taxes directly reduce the amount of earnings individuals and businesses take home. When income taxes are deducted from wages or profits, the remaining funds available for personal consumption, savings, or investment shrink. For individuals, this reduction in disposable income impacts spending habits, especially in lower-income households, where a larger proportion of income is dedicated to essential needs. For businesses, high income taxes can reduce the funds available for reinvestment, leading to lower growth potential, fewer job opportunities, and stifled innovation.

Sales taxes, on the other hand, reduce disposable income at the point of consumption. Every time consumers make a purchase, they pay an additional amount in taxes, effectively raising the price of goods and services. This leads to a decrease in the real value of their income, as they can afford fewer goods or services for the same amount of money. This impact is more pronounced for lower-income individuals, who spend a greater percentage of their income on goods subject to sales tax, resulting in a heavier financial burden and diminished economic flexibility.

In both cases, the reduction in disposable income leads to broader economic inefficiencies: Reduced disposable income means less money available for discretionary spending, which drives a significant portion of economic growth. As consumers tighten their budgets, demand for goods and services decreases, leading to slower economic activity.

When businesses face higher income taxes, they may reduce their investments in new projects, hiring, or expansion. Similarly, when individuals have less disposable income due to high sales taxes, they may save less or invest less in long-term assets, further slowing economic growth.

Both types of taxes disproportionately affect lower-income households, compounding the issue of income inequality. The reduction in disposable income leaves lower-income individuals with fewer resources to save, invest, or spend on non-essential items, further exacerbating economic disparity.

Together, these factors highlight how income and sales taxes, while necessary for funding government operations, impose significant economic inefficiencies by reducing disposable income, stifling consumer demand, and limiting investment opportunities.

Complex Tax Code

One of the most significant inefficiencies of both income and sales taxes is the sheer complexity of the tax code. The U.S. tax system, particularly for income taxes, is vast and convoluted, with thousands of pages of rules, regulations, and exceptions that make it difficult for individuals and businesses to comply without professional assistance. This complexity creates inefficiencies in several ways.

First, the extensive and intricate nature of the tax code increases the cost of compliance. Most individuals and businesses cannot navigate the tax code on their own, necessitating the use of accountants, tax preparers, and legal professionals. These compliance costs are particularly burdensome for small businesses and middle-income households, diverting resources away from more productive economic activities. In fact, the U.S. tax code is often cited as being tens of thousands of pages long when including all associated regulations, with the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) itself spanning over 2,600 pages.

Second, the complexity of the tax system encourages tax avoidance and evasion. High-income earners and corporations, with access to sophisticated financial advice, can exploit loopholes, deductions, and credits that reduce their effective tax burden. This not only reduces the amount of revenue collected by the government but also places an additional burden on those who cannot afford such strategies, further contributing to inequality. The result is a tax system that, while appearing progressive on paper, often functions regressively in practice, with wealthier individuals paying a lower effective rate than middle-income taxpayers.

Moreover, the tax code’s complexity complicates government enforcement efforts. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) must dedicate significant resources to auditing, investigating, and managing compliance, but the sheer scale of the system means many cases go unchecked. This reduces the overall effectiveness of tax collection, as individuals and businesses who find ways to underreport income or exaggerate deductions often face little risk of being caught. Estimates of the tax gap, the difference between what taxpayers owe and what is collected, run into the hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

Sales taxes, while simpler in theory, also face complexity in application. Different states, and sometimes localities, have varying rates, exemptions, and rules about what is taxable, creating a patchwork system that is difficult to navigate, especially for businesses operating across state lines. With the rise of e-commerce and digital products, sales tax laws have had to evolve to address new types of transactions, further complicating the system for businesses and consumers alike. This leads to inefficiencies as businesses spend more time and money ensuring compliance with multiple tax jurisdictions.

In conclusion, the complexity of both income and sales taxes creates significant economic inefficiencies. It increases compliance costs, fosters inequality through tax avoidance, and complicates enforcement, all of which undermine the overall effectiveness of the tax system. This complexity highlights the need for a more streamlined and transparent approach to taxation.

Undermining Public Trust

The complexity and perceived unfairness of income and sales taxes contribute significantly to the erosion of public trust in the tax system. When people see tax laws that are opaque, difficult to navigate, and seemingly skewed in favor of wealthier individuals and large corporations, confidence in the system’s fairness diminishes. This distrust can manifest in various ways, from widespread tax avoidance and evasion to growing political resistance to tax reform efforts.

For many taxpayers, income tax compliance feels unnecessarily burdensome due to the intricate rules, deductions, credits, and exceptions that make filing taxes a daunting task. The average person often feels disconnected from the tax code and reliant on expensive professionals just to meet their obligations. This complexity fosters a sense of alienation and unfairness, particularly when high-income earners are seen using legal tax avoidance strategies, like offshore tax shelters or complex deductions, to minimize their liabilities. The perception that the wealthy can pay far less than their fair share undermines public confidence in the entire system.

Sales taxes, while generally simpler, also contribute to mistrust, particularly because of their regressive nature. Lower-income households, who spend more of their income on taxable goods and services, are acutely aware of the disproportionate burden they carry. Meanwhile, exemptions and loopholes within sales tax structures, such as exclusions for certain luxury services, exacerbate the feeling that the system benefits those at the top more than those struggling to make ends meet. This imbalance fosters resentment and increases the belief that the system is rigged against ordinary taxpayers.

Moreover, the cyclical nature of tax revenue, which often declines in economic downturns just as public needs rise, further erodes trust. During recessions, governments may be forced to either cut public services or borrow more money, both of which can trigger public frustration. Cuts in services are particularly damaging, as they often hit the most vulnerable communities hardest, fueling the perception that the tax system does not work for everyone equally. This leads to growing disillusionment with government institutions and broader skepticism of taxation as a legitimate and equitable means of funding public services.

Additionally, high-profile cases of tax evasion, particularly by well-known public figures or corporations, add to the perception that the tax system is not enforced equitably. When ordinary people see high-income earners or large businesses facing little to no consequences for underreporting income or exploiting tax loopholes, they may feel less compelled to comply themselves. This environment encourages further tax evasion and avoidance, exacerbating the tax gap and further undermining public trust in government’s ability to ensure fairness in the tax system.

In summary, the complexity and inequities embedded in both income and sales taxes contribute to a widespread erosion of public trust. Whether through the perception of unfairness in how taxes are applied, the visible avoidance strategies of the wealthy, or the economic hardships imposed during downturns, the tax system is seen as disconnected from the needs and realities of ordinary taxpayers. This growing mistrust makes it harder to implement necessary reforms and can lead to increased resistance to taxation as a tool for funding public services.

The Transaction Tax

One compelling alternative to the existing tax system is a transaction tax. The latest available data shows that total transactions in the U.S. economy amount to $7.6 quadrillion annually. These transactions span both financial economic circulation (such as stock trades and large financial transfers) and productive economic circulation (spending on goods and services). Meanwhile, government spending in 2020 was $6.7 trillion according to the FRED series FGEXPND, which tracks federal expenditures.

By implementing a transaction tax of less than 0.09%, the government could raise enough revenue to completely fund all federal spending. This rate is extremely small, such a tax would amount to just $90 for every $100,000 spent annually, replacing not only income taxes but also potentially eliminating the need for other forms of taxation.

A key advantage of this approach is its administrative simplicity. Most transactions, especially in the financial sector, already involve fees, and adding a minimal tax would be straightforward. There would be no need for complex tax returns, income reporting, or the thousands of pages of regulations currently required to administer the income tax system. The transaction tax would be applied automatically at the point of transaction, largely going unnoticed by individuals.

For those spending $100,000 annually, the tax would be $90 under this system, and they would pay no income tax. For individuals at the lower end of the economic spectrum, the impact would be even less significant. Someone spending $10,000 a year would only pay $9 in taxes, making it one of the most minimal and painless ways to fund government spending.

To replace all levels of government spending, including state and local, the tax rate would need to rise to around 0.12%. This would amount to $120 for every $100,000 spent, a modest increase that would still allow for the elimination of all income, sales, and property taxes. Such a small tax on transactions could be sufficient to cover all federal, state, and local government expenditures.

In fact, by increasing the transaction tax rate to around 0.25% (25 cents for every $100 spent), the government would not only be able to maintain its current level of spending but also significantly expand services. This would provide enough revenue to fund all infrastructure projects, offer universal healthcare, provide free higher education, and even establish a Universal Basic Income (UBI). This modest rate increase would allow the government to undertake all the social programs often deemed too expensive, without placing a burden on individuals or corporations.

In addition to its domestic benefits, a transaction tax would have a profound impact on foreign investments. The elimination of income taxes would make the U.S. an even more attractive destination for international businesses and investors. Companies from around the world would clamor to relocate operations and earn income in the U.S., driven by the allure of a tax-free environment for profits. This would lead to a significant inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI), bolstering U.S. industries, creating jobs, and stimulating overall economic growth.

While other countries may eventually follow suit by adopting similar tax structures, the U.S. would likely enjoy an initial period of competitive advantage, attracting global capital on an unprecedented scale. This influx of investment could further boost economic production, as companies expand their operations, invest in new technologies, and increase output to meet rising demand in a tax-efficient environment. The result would be a vibrant, more productive economy, with increased innovation and stronger global competitiveness.

This added layer of economic stimulation highlights the broader potential of a transaction tax to reshape not just domestic economic conditions but also the international business landscape.

Conclusion

A transaction tax presents a feasible, efficient, and fair alternative to the current tax system. It eliminates the need for complex regulations and compliance, generates ample revenue for government functions, and does so with minimal impact on individual spending power. This approach could transform public finance and enable the government to meet both its current and future obligations without the administrative headaches and inequalities inherent in today’s tax system.