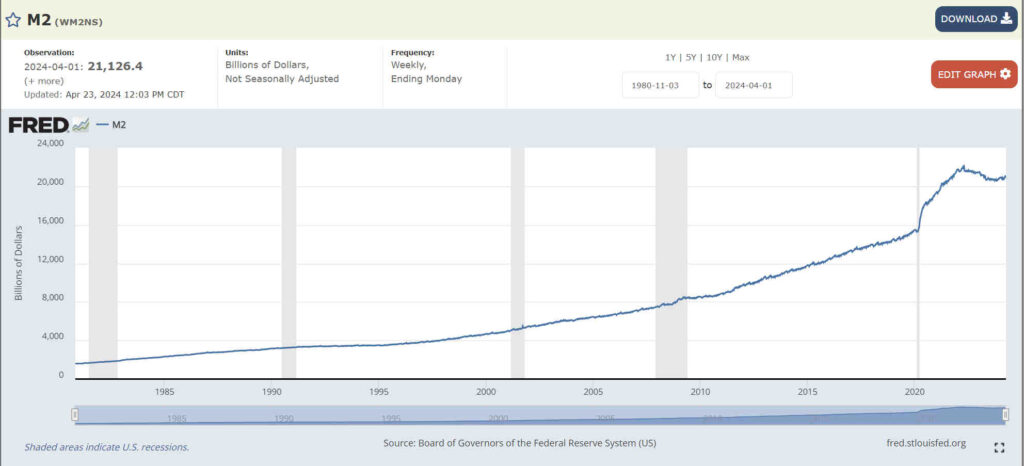

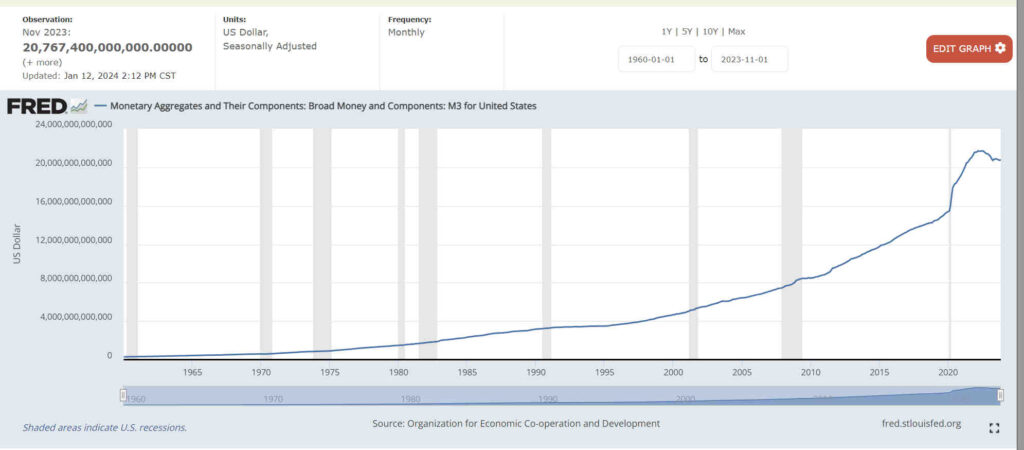

The top graph shows M2, the amount of money that generally circulates in the economy. The bottom graph shows M3. M3 is supposed to show all of M2 plus the amount in large time-deposit savings accounts or money market accounts (over $100,000). There is so little difference between these two values that it appears large account reporting is totally eliminated from M3. The formal reporting of M3 was discontinued by the Fed in 2006 because it was considered unreliable. This report is said to be a composite created by compiling economic data from various sources. This totally misleading report of M3 is picked up by reputable financial websites as the accurate value of M3. For purposes of this website, the inclusion of debt securities of less than 2 years might muddy our evaluation of money creation because, although these can be converted into spendable money, they were not part of money created by banks or the Fed. Repos, which are also included in M3, have already converted a debt instrument into money by the Fed. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WM2NS https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MABMM301USM189S

Money Creation

We work to earn money. The money we earn pays the debt our employers owe. We take the money we earn to pay our rent or mortgage, we use it to buy food and clothing. It appears that money repays debt. So, when I say, “All money is debt,” your immediate response is no, it repays debt.

A more complete statement of money as debt would be that modern money has its origins in debt. As a consequence, the more money that circulates in a society, the more society is in debt. To understand that, we need to look at the creation and destruction of money.

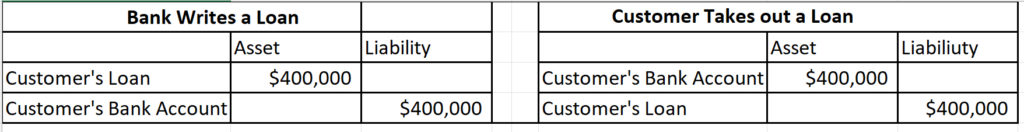

When a bank writes a loan, it creates new money which circulates throughout the economy. That money clearly has its origins in debt. The article linked to in this paragraph reveals that despite most economist’s beliefs, the bank does not loan out depositor’s money. Figure 1 shows hypothetical balance sheet entries based on Werner’s article.

Figure 1. The left side represents balance sheet entries for a bank, the right the balance sheet entries for the bank’s customer. The loan is an asset to the bank but the money placed in the customer’s bank account is a liability for the bank. That money is an asset to the customer but the loan is a liability for the customer. Werner’s paper indicates that no access to other assets are made when writing a loan (i.e. no depositor’s funds are used.) New money is created and placed in the customer’s bank account. From there it circulates throughout the economy and its origins as debt are lost.

Money is already circulating throughout the economy. This new money gets spent (most often in the same meeting that created the loan) and becomes mixed with money already circulating. That new money circulates until its origins are lost. The money that circulates is an asset, but there is an underlying debt that has a claim on the money that was created. It is the responsibility of the borrower to reclaim enough of the circulating money to repay both the principal and the interest of that loan.

Money Destruction

Looking at debt creation from an accounting perspective offers insight in why we view money in different ways. When we describe money as debt, we are looking at money from the viewpoint of its creation. Without the debt, the money would not exist. Each time new money circulates, it means another debt has been written.

Money is both an asset and a liability. The recipient of the money views it from the asset side of the ledger while the person owing money looks at it from the liability side of the ledger. As money circulates throughout an economy, we lose sight of its origins in debt.

When a borrower makes a loan payment, the loan payment includes both principal and interest. The principal part of the loan payment destroys that amount of money circulating in the economy. This destruction isn’t apparent. After all, both the principal and interest go to the bank where they use that money to pay wages, purchase office supplies, pay dividends, and buy other assets. It appears that the bank just continues the circulation of the money that had been created.

Let’s look at a couple scenarios that demonstrate the destruction of money by repaying principal. Assume you took out a loan and put that money in your bank account. We’ve seen from the accounting entries above that the bank created the money to put it in your account. Later in the day, you get cold feet and repay the entire loan. Now there is nothing in your bank account and the loan is extinguished. That repayment destroyed the money that was created by taking out the loan.

If you waited a month and then repaid the loan, you would have to come up with more than the money that was originally put into the account. You would owe interest. To pay that, you’d have to capture some of the money that circulates through the economy.

What is the difference, then, if that repayment of the loan happens over 10 years or a single day or a month. The principal part of the loan payment destroys money while the interest that you incur over the length of the loan has to be captured from circulating money.

In another scenario, imagine we stop time and gather together all debtors and all the people that have the money that was created. To cancel all the debts, we could collect all the money together. Since the money was created by the loans written, there would be enough money to pay back the principal of all the loans combined. Even if some of the people had paid some of that circulating money to pay interest on their loans, the bank would recirculate that money back into the economy or save it somewhere. Since we are collecting all money in existence, there will be enough to pay back all the principal of all of the loans.

But there is still a problem with the last period interest. In an economy the size of the US, there is over $20 trillion in circulation. (there is a lot more than that but the Federal Reserve Economic Data is hiding M3 values from the public.) If average interest rates are 6% and we assume some due dates are nearly at the date we stopped and other dates are due a month later, we can take 3% as the average. Divide that by 12 and we get .25%. The interest bill, the shortfall to settling the debts, comes out to $50 billion.

What this stop-time experiment shows us is that each month, about $50 billion of additional borrowing is needed to pay the interest on the money that was created as debt. Since the monthly payments also include principal, which reduces the money supply, a total of about $220 billion in new borrowing is needed just to keep the money supply at a steady level. Any less and the money supply decreases and the economy stagnates.

Government Creation of Money

US law requires the treasury to have money in its account before it spends. Prior to 2008, the treasury account kept its account balance to about $5 billion and went to great lengths to maintain that amount. (See this. Stephanie Bell married and changed her name to Stephanie Kelton, and is the author of “The Deficit Myth,” (required reading if you want to understand MMT.))

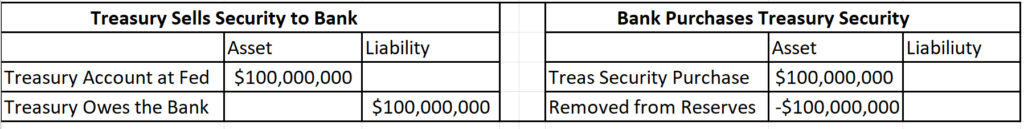

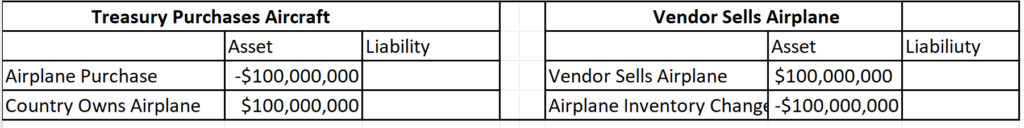

This requirement to have the money in the account before it spends means that the treasury must borrow to preload the account or to replenish the amount it spends. Figure 3 shows hypothetical balance sheet entries that demonstrates that the end result of treasury borrowing then spending is to remove it from one bank’s reserve account and to place it in another bank’s reserve account.

Figure 3. The top two hypothetical balance sheet entries represent the treasury borrowing money from a bank by selling a bond to the bank. This transfers existing cash from a bank’s reserve account to the treasury’s account in exchange for a loan document (bond or T-bill). The bottom two hypothetical balance sheet entries represent the treasury spending money for an airplane. The treasury removes money from its account and it gets an aircraft in exchange. The airplane manufacturer gets money but removes the airplane from its inventory. There are more complications and these transactions may occur over time and between many banks and vendors, but the consequences would be as summarized.

Treasury spending does not create new money as most of us view money. It does create a new debt document that resides in a special account the bank maintains at the Fed. The bank that purchases the security is usually one of 24 dealers that are generally part of a large bank.

The dealers buy and sell these treasuries as part of their business. If a private buyer acquires a treasury security, that buyer cannot (generally) spend that security in the economy. The buyer has to either sell that security to another buyer or to the Fed and then there is money to spend into the economy. If the Fed buys the security, it creates new money that goes into the seller’s bank’s reserve account and the seller’s bank account is credited with the money. If anyone else buys the security, no new money is created.

Just like bank created money, the treasury security that was created by government spending is destroyed when the debt is repaid. (See the blog post, Reserve Barrier for a complete explanation of government spending and money creation.) To repay the debt, the government taxes people and businesses. That removes money from the taxpayer’s bank’s reserve account and the bank debits the customer’s account.

Conclusion

Banks create money by writing a loan. The more money that exists in the economy, the more debt has been created. The interest on that increased debt means that our economy must produce more real wealth than the increase in interest in order to keep our standard of living moving up. Since the borrowed money funds production of expendables as well as real wealth, the economy can never produce more wealth than the rise in interest costs. The more money in an economy, the harder it is to overcome the interest payments due.