Money Creation, Destruction, Circulation, and Ensconsment

Introduction: Four Types of Money

In our discussion of fiat money in chapter 1, we didn’t consider different forms of money. Joseph Wang, in his book, “Central Banking 101,” defines four different kinds of money: wallet money, bank account money, bank reserves, and treasury securities. We are all familiar with the first two. The second two, most have heard about but never considered them as money. For a complete understanding of how money is created, destroyed and circulated, we need to understand the complex interactions between these four money types.

Wallet Money

Wallet money refers to the physical banknotes we carry around in our wallets. In our discussions of fiat currencies, the banknotes we mentioned were a form of wallet money. Only a small fraction of money exists in the form of wallet money. Many websites cite a value of 3% of the total money existing as wallet money. Using the Federal Reserve Economic Data website and comparing currency outstanding with either the M2 numbers or the discontinued M3 numbers, that division yields numbers closer to 11-12%. (M designations are different measures of the money supply,)

The amount of wallet money being used is declining in favor of credit card transactions. Authorities would rather eliminate wallet money altogether since its use in illegal activities prevents tracking it. Wallet money circulates outside of the banking system and can easily be transferred from person to person without records. Part of the motivation in creating Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) is to reduce further the use of wallet money.

While wallet money also includes coins, the amount of money circulating as coins is truly an insignificant value. For our discussions the only significance of coins is that they are the only money that circulates that is not created through lending.

Bank Account Money

Bank account money exists as computer entries at our banks. This forms most of the money that circulates in the productive economy. Bank account money can easily be converted to wallet money by withdrawing money from a bank account as “cash.” Converting it back into bank account money is just as simple; presented with “cash” the bank can add it to a bank account.

The wallet money and bank account money take different trajectories in the creation/destruction cycles. Wallet money creation and destruction involves interactions with the central bank while creation and destruction of bank account money involves only a bank’s accounting entries.

Bank Reserves

Bank reserves are a form of money that operates behind the scenes of our everyday financial transactions. These reserves are held at the central bank, not as accounts at the commercial banks. Any changes to the reserve balances can only be made by the central bank. All money in the reserve accounts is created by the central bank.

The purpose of bank reserves is to provide commercial banks with enough money to withstand temporary increases in demand for money from depositors. The central bank sets up the requirements for reserve levels based on the level of risk the commercial bank faces. These reserve requirements are a percentage of total deposits, not total risks the bank faces.

Since 2008, the U.S. banks’ reserves have risen dramatically. The Federal Reserve (Fed) has decided to operate in an “ample reserve” regime. This gives them more flexibility as they manipulate interest rates.

As a side note about bank reserves: if you search the Internet about money creation, you will invariably find the inaccurate account of central banks creating money in reserves and through the magic of fractional reserve banking, commercial banks can create a multiple of the original injection into reserves. The multiplication rate is the inverse of the reserve rate. The real process of commercial banks creating money is simpler than that.

Treasury Securities

Treasury securities are not something most of us would recognize as money. They are not typically used for economic purchases. They circulate widely as a form of money in financial markets. They play an important role in the financial systems and interact with other forms of money in complex ways.

Treasury securities are generated by government borrowing. Bills (or T-Bills) are short term loans to the government. They mature in four weeks to one year. Notes (or T-Notes) are issued in either two, three-, five-, seven-, or ten-year periods. Bonds mature in twenty to thirty years.

T-Bills are sold at a discount at an auction. At the auction, the price paid is a discount from the face value of the bill. The winning bidder is the one who bids the highest price (lowest yield.) The difference between the auction price and the amount received at maturity is the interest paid. T-Bills can also be purchased through a bank or broker.

T-Note bids specify a yield. The lowest yield is the winner (purchased at the highest price). In the T-Note auctions, you can specify that you are a non-competitive bidder. This means you will accept the yield of the winning bidder. All the T-Notes sold at any one auction provide the same yield. T-Notes can also be purchased through a bank or broker.

Bonds are the savings bonds that helped finance the government during the depression and helped finance WWII. Savings bonds can be inherited but cannot be transferred. They are issued to the purchaser. Savings bonds are available only through the treasurydirect.gov website.

The Fed is prevented from purchasing these treasury securities directly from the treasury. Once the security has gone through these auctions, the Fed is allowed to purchase those securities from private buyers. In rare cases, the Fed is allowed to purchase securities directly from the treasury. This happened after 9/11 shut down the financial sector.

Creation

Creation of Wallet Money

When the media report on excessive creation of money they often show massive sheets of $100 bills running through the press. Ramping up the printing presses is hyped as the cause of the inflation we are experiencing. The reality is that the creation of wallet money is one of the least inflationary aspects of all money creation.

The Fed keeps track of demand for physical currency. Each year they decide how much is needed and they place an order with the Treasury’s Bureau of Printing and Engraving. The Treasury prints the bills, and the Fed pays for the printing and transportation costs (about six cents per bill regardless of its face value.).

The bills held by the Fed are listed on their books as liabilities at their face value (not the printing cost); they owe them to the public. The asset side of the books are treasury securities they pledge out of their purchases from the open market.

When a commercial bank needs more currency, it orders it from the Fed and an armored car delivers it from its district federal reserve bank. The Fed deducts the face value of the bills delivered from the bank’s reserve account. For the bank, this is just an exchange of assets.

When a customer wants cash, the cash comes out of their bank account. To the customer, this is just an exchange of assets. This introduction of wallet money into the economy is an exchange of assets. It does not inflate the money supply.

Not all the printed wallet money goes to the U.S. banks. As the world’s reserve currency, much of the wallet money goes overseas. The Fed estimates that one half to two thirds of the printed wallet money goes overseas.

While the images of running printing presses makes a good visual, the real inflationary money creation comes from the creation of bank account money.

Creation of Bank Account Money

The creation of bank account money is where most of the money that circulates in the economy comes from. This is the lifeblood of our modern economy, and its origins are a surprise to even many economists. Banks create it when they write a loan.

The accounting entries show that when a loan is written there are two entries. One is the liability for the money that is placed in the borrower’s account and the asset is the loan document. There is now money in the borrower’s account ready for them to spend. There are no entries that obligate other deposits as surety for the loan. The money was created out of “thin air,” to use the phrase most used with this process.

On the Internet you may find references to “fractional reserve lending.” This idea is that the central bank creates money when the government spends and puts it in bank reserves. The bank must keep a fraction in its reserve account, but the rest can be lent. That newly lent money is deposited in another bank which must keep a fraction in its reserve account but can lend out the remainder. In this way the money supply multiplies the original amount created by the central bank by the inverse of the reserve fraction.

This explanation makes it sound so dependent on that initial reserve deposit. It is not. A deposit from another bank adds money to the bank’s reserves (an asset) and money into the depositor’s account (a liability.) There is no net increase in the bank’s net worth based on deposited money. Besides, lending does not attach deposits; it creates new money.

The determining factor in writing a new loan is the health of the balance sheet of the bank. The bank must maintain certain capital ratios, essentially maintaining a cushion of their own money or other assets to protect against failed loans. A deposit from another bank requires only a fraction of that deposit to be held in reserve so the rest of that increase in the bank’s reserves is in excess of the requirements. The amount of a bank’s excess reserves is certainly part of the health of the balance sheet so additional lending can be done based on the excess reserves.

But what makes this implausible as an explanation of the expansion of the money supply is that diverting reserves to one bank means decreasing reserves at another. Whatever increase in excess reserves one bank receives from the exchange, another bank’s excess reserves is reduced, limiting any monetary expansion. if a bank is relying on the level of deposits to determine their ability to lend, what happens when the depositor spends the money in their account. If the bank barely has enough money in reserves to cover their deposits, now the loss of that depositor’s money from their reserves means the bank needs to suddenly find that same amount of money from somewhere else. They can borrow from the Fed or other banks, but there are consequences, especially if the lender is the Fed. This puts a stigma on the bank if they must rely on Fed lending.

Deposits are far too volatile to base lending decisions on them. The capital ratios require something the bank can better control, like treasury securities.

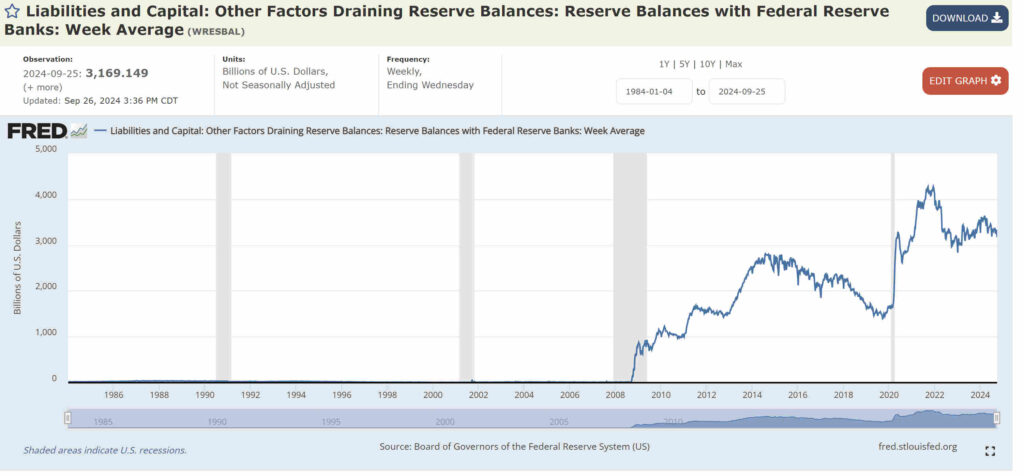

This entire scenario of lending against reserves has been made moot by the Fed’s “ample reserves regime” that was instituted after 2008. Total bank reserves went from levels of $30 to $40 billion prior to 2008 to a peak of $3.2 trillion in June of 2020. The Fed has discontinued reporting on the total reserve levels shortly after that peak. In an ample reserve regime, the banks are no longer operating where they require a deposit to raise their excess reserves so they can lend more.

Banks are one of the most highly regulated businesses. The regulators can shut them down or force the sale of the bank if the bank does not maintain a healthy balance sheet. After all, banks create our money and trust in money is vital to maintaining its value.

When the bank writes the loan it creates the principal amount. But it doesn’t create the money to pay the interest. Since all the money is created this way, society, collectively, must always be indebted. If we were to freeze time and count all the money that exists through bank lending, it should match the total remaining principal of all existing bank loans. After counting all the money that exists, what is missing is the interest payments for the next payment period.

While this appears to be a minor problem, as economies grow, society goes deeper into debt. The total corporate and household debt in the U.S, is nearly $34 trillion. That means a single month’s interest payment at an average interest rate of 6% is $170 billion ($2 trillion per year). This is society’s cost of maintaining our money system.

Creation of Bank Reserves

Bank reserves are accounts set up at the central bank for commercial banks. All the money transactions at the Fed go into or out of reserve accounts. Money placed or removed in those reserve accounts influences money that circulates in the general economy, but it reflects the money the central bank created.

This creates a “reserve barrier” that will be discussed extensively in chapter 7. Joseph Wang, in his book, “Central Banking 101,” compares it to an iron wall.

Just like commercial banks, the central bank can create money out of thin air. The money the central bank creates increase balances in the reserve accounts. These changes in reserve balances are then reflected in the account balances for either the bank itself or its customers.

Communication between banks is also done through the reserve accounts. If you pay your phone bill, the money you transfer to the phone company results in a reduction in your bank balance, an increase in the phone company’s bank balance, and instructions to the central bank to transfer reserves from your bank’s reserve account to the phone company’s bank’s reserve account.

While Fed cannot directly purchase U.S. treasury securities from the treasury, after those securities have been auctioned to the public, the Fed maintains an active trade in treasury securities sold to and purchased from the public. It is through these trades that changes are made to the overall reserve balances.

When the Fed purchases a treasury security, it increases the balance of the seller’s bank’s reserve account. The bank then increases the balance of the seller’s bank account. In this way, the Fed can increase the amount of money in the economy.

When the Fed sells a treasury security, it decreases the balance of the buyer’s bank’s reserve account. The bank then decreases the balance of the buyer’s bank account. In this way the Fed can decrease the amount of money in the economy.

The Fed conducts, typically, over $4 trillion in daily trades in the “repo” markets. The term, “repo,” is short for “repurchase agreement.” In a repo, one party agrees to purchase an asset and then sell it back to the original owner for a slightly higher price. Most of these repo agreements are designed to purchase the asset on one day and sell it back the following day. A “reverse repo” is a trade in the opposite direction. In this case the first party sells an asset with the agreement to repurchase that asset for a slightly higher amount.

When the Fed participates in the repo markets, its repos increase the amount of money in bank reserves which is reflected as increased money in the general economy. The Fed participation in a reverse repo decreases money in the general economy. By adjusting the ratio of repos to reverse repos, the Fed can control the amount of money introduced into the economy.

In chapter 7 we will delve into the intricacies of finance and production, but for now, realize that these changes in circulating money are not the most important factor affecting the direction of the productive economy. A more important role of the Fed in the repo markets is in setting the interest rates in those trades (the difference in price between the purchase and repurchase.) The interest rate changes influence the lending environment of commercial banks. Those interest changes are a more important factor in changing the direction of the productive economy.

Changing interest rates is a slow method of changing the direction of the economy. In chapters 10 and 11 we will propose faster ways of turning around the economy.

Creation of Treasury Securities

A treasury security is a loan document that the government issues when it borrows money so that it can spend. These loan documents are either a bill, a note, or a bond. What distinguishes them is the term of the loan. Notes are loans of less than a year, Bills are loans of 2 years to 10 years, and bonds are loans longer than 10 years.

While the U.S. constitution (Article I, Section 8) grants the federal government the power to coin money and to regulate its value, the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 turned over the power of creating money that is not coins to the Federal Reserve. The Fed also regulates the money’s value. This constitutional article is why coins are the only money introduced into our economy as debt-free money.

While our government could act as a bank itself and create money out of thin air like the Fed and the commercial banks do, it does not create money; it borrows to spend. All the borrowing and spending of the government is on the Fed side of the reserve barrier.

The U.S. treasury has an account at the Fed like a commercial bank’s reserve account. This account, the Treasury General Account (TGA), must have money in it before the government is allowed to spend.

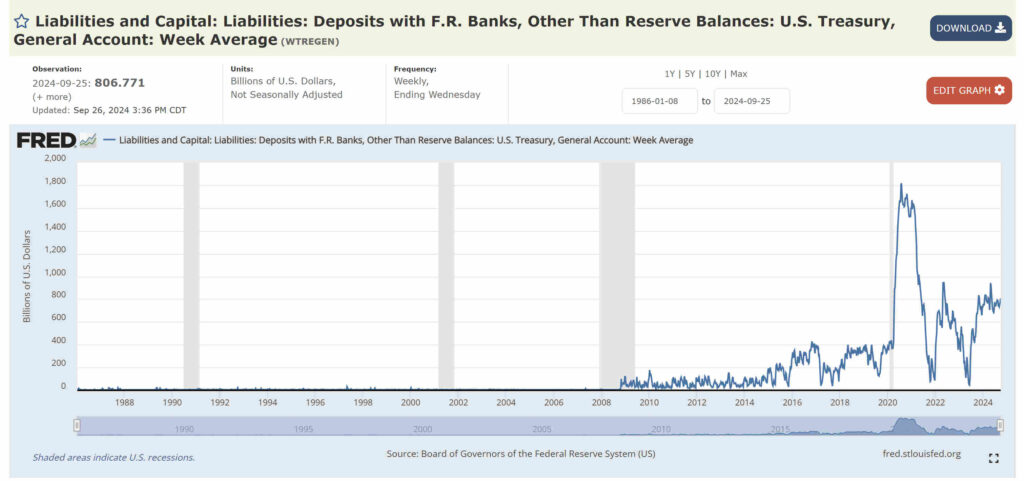

This graph shows the TGA balances from 1980 to 2024 (FRED graph D2WLTGAL). Prior to 2008, the TGA balance was kept around $5 billion. That peak in 2020 was almost $1.8 trillion. We will discuss that peak a little more in chapter 7.

When the treasury decides it needs money for upcoming spending, it creates treasury securities. The treasury presents them to the Fed for an auction. The Fed, through its Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) conducts the auction. Most of these offerings are purchased by large banks and institutional investors, but anyone can purchase treasuries through treasurydirect.gov. Some others can be purchased through banks and brokers.

Upon the sale of the securities through the auction, the purchasers’ bank accounts are reduced, those customers’ banks’ reserve accounts are reduced, and the total of those reserve account reductions goes into the TGA. Now the government has money to spend.

The purchasers of the securities can either save those securities as investments or trade them for other financial papers. Very few are used for purchases in the broader economy.

When the government spends, the Fed transfers money from the TGA to the vendor’s bank’s reserve account and the vendor’s bank account is increased. If the borrowing and the spending is the same amount, there is no net change in total reserves. Yet, there are treasury securities in an amount equal to the spending and those securities circulate within financial circles as money. This is the source of the MMT claim that government deficit spending creates money.

Destruction

Destruction of Wallet Money

Paper money wears out, gets damaged, or dirty. Throughout the lifecycle of wallet money, as the money circulates through banks, its physical state is evaluated. Bills that are dirty, torn, or excessively worn are sent back to the Fed for further evaluation. Bills that are sent back to the Fed because of a bank’s excess stock are also evaluated to see if they are counterfeit or ready to be replaced.

The Fed has sophisticated high speed machines that can do these evaluations quickly. Counterfeit bills are sent to the Secret Service for investigation and prosecution. Bills that can be reused are stacked in vaults ready for the next time a bank requests wallet money. For every bill destroyed, the Fed orders a replacement from the Bureau of Printing and Engraving.

The money to be destroyed is shredded extremely finely. This shredded money is then disposed of in various ways. Some of this shredded money is compacted into bricks and sent to landfills. Some shredded money is incinerated in power plants.

This process of destruction and replacement does not change the overall supply of wallet money. What it does is ensure that the supply of wallet money circulating is in good shape. This cycle of destruction and renewal keeps our wallet money functional and secure.

Destruction of Bank Account Money

Most people have no problem understanding how the bank creates money by writing a loan once the process is explained to them. It is harder to grasp that when you make a payment on your loan, the principal part of that payment is destroying that amount of circulating money.

What most people say when confronting this news is that “The money has left the bank after the borrower spends it. It is now circulating and out of the reach of the bank that created it. Its circulation guarantees its survival.”

But money is fungible. This means that the bank account money in your account is identical to the bank account money that was originally in your account. It has been substituted by circulating bank account money.

To further understand how this repayment destroys money, imagine you take out a loan for $100,000. As soon as the loan is written, there is $100,000 that didn’t exist before. Imagine that an hour later, before you spend the money, you got cold feet and went back to the bank and repaid the loan.

In this case, the accounting entries that created the money would be reversed and the bank’s accounts and your accounts would be the same as if you hadn’t taken out the loan at all. It is the account entries reversing the original creation entries that destroy the money.

When you make loan payments, the bank is making the same destruction entries only a little bit at a time. The principal part of your loan payment is entered into the accounting system so that it reverses a fraction of the original accounting entries. The interest part of the loan payment has different account entries that do not destroy money. Over the life of the loan, these smaller principal payment accounting entries total up to the same as when you immediately repaid the loan.

There is another thing that most people don’t realize, even when they accept that loan repayment destroys money. When someone defaults on a loan, the principal remaining on that loan is the amount of money destroyed by the bank writing off the loan.

There is one other way bank account money is destroyed, but we will explain that in the section below on the destruction of treasury securities.

Repayment of debt destroying bank account money has societal implications. We’ve seen that wallet money is just converted from bank account money into a different form. It is the bank account money that drives all our economic activity. But now we’ve seen that repaying debt or defaulting on debt destroys money.

What if we were to all accept the common conservative message to lift ourselves up, repay debt, and all live debt-free? Long before we got to the point of reducing even a fraction of our total outstanding debt, the economy would find itself in an extreme recession. Not only would debt repayment reduce the money supply but the resulting defaults due to economic retraction would quickly destroy large chunks of money.

The functioning and expansion of our economy relies on maintaining debt levels. Repaying debt destroys money and reducing circulating money reduces economic activity. Total new borrowing must at least be in an amount to replace money destroyed by debt repayment or the money supply shrinks.

In chapter 11 we will show that our money system does not need to be designed where constantly growing debt is needed to grow an economy. Reforming this aspect of our money system has profound implications for all of society. For one thing, it would make the conservative admonitions something we could all heed.

So, the next time you take out a loan or make a loan payment, realize that you are participating in a large-scale cycle of creation and destruction of society’s money supply. Bank account money starts it all by writing the loans we all take out.

Destruction of Bank Reserves

What we learned about bank account money applies to both bank reserve money and treasury securities. When the Fed creates money, it creates money out of thin air, just like a commercial bank does. This money, however, stays in reserve accounts until it is destroyed.

When the Fed creates the money to be placed in reserves, it exchanges some sort of debt instrument in exchange. Most often these debts are treasury securities, but, especially after 2008, these may be commercial debt. One primary source of commercial debts for the Fed are the mortgages that Freddie Mae and Freddie Mac lend or purchase.

These debts, while not written by the Fed, still function as the underlying debt instruments supporting the money created in reserve accounts. Similar accounting entries, as those made in commercial banks when writing loans, are made at the fed to support the reserves creation. Like the destruction of money by repaying principal in bank account money, so, too, does principal repayment on the loans held by the Fed reverse accounting entries that destroy bank reserve money.

The graph above shows the total of all bank reserves (Federal Reserve Economic Data graph WRESBAL. For nearly a century, bank reserves were maintained at levels under $40 billion. Those peaks in 2022 reached $4.27 trillion.

In 2008, the Fed embarked on increasing reserves through quantitative easing (QE). With QE, the Fed purchased massive amounts of commercial debt, largely toxic debt that the banks would have needed to write off. As we have seen above, writing off debt destroys money circulating in the economy. By the Fed purchasing those debts, the banks were able to avoid writing down the debt. The Fed prevented a massive drop in circulating money.

Even if the debts underlying the massive increase in reserves are not repaid, if the Fed does not write down the debts as insolvent, the reserves stay in the reserve accounts. The Fed has the wherewithal to delay writing down those debts for long periods, the banks do not.

The Fed could have achieved the same result of protecting the money supply from massively imploding by purchasing those toxic debts from the banks and keeping the homeowners in their homes while the Fed sorted out the problems created by the mortgage-backed derivatives.

Mortgage-backed derivatives had been created by purchasing mortgages that were very likely to fail. The derivatives were constructed by breaking up the mortgages into “tranches.” Each tranche consisted of just a piece of the mortgage, for example maybe just the first five years of payments. The further down the timeline, the less likely it was that the mortgagee would still be making payments.

The rating agencies had long known that by bundling many mortgages together, the likelihood of all of them failing at the same time was minimal. Those constructing the derivatives got the less risky tranches to hold AAA ratings and were sold to investors. What those constructing the derivatives failed to mention to the rating agencies was that those loans were selected because of their high risk. High-risk debts are much cheaper than low-risk debts.

This scheme created a market in high-risk debt. It didn’t matter how risky a debt was, there was a market for it. The loan officers were paid loan origination fees, and the banks didn’t care that the loans were risky because by the time the loan failed, they had already offloaded the debt to the derivatives market.

The housing market implosion of 2008 was caused when those loans began failing. The loans were often written so that payments were less than the accumulating interest and the interest was lower than market interest. After a period, generally three years, the loan would revert to payments that would start repaying principal plus interest and the interest rate would then jump to the market rate.

Since not all the interest was being paid by the loan payments, the borrower not only had a jump in rates and payment conditions, but the principal amount was larger than the original loan by the amount of the accumulated unpaid interest. Few could make the payments, and refinancing was out of reach because the principal balance relative to the value of the property no longer met down payment requirements.

This lengthy explanation of the problem is required to understand the problems facing the Fed. By dividing the mortgages into tranches, the ownership of the property was in question. Normal mortgages that remain intact bestow ownership of the underlying property to the owner of the loan until the mortgage is repaid. By breaking the mortgage into tranches, who owned the underlying property? Unraveling this mess would take years.

This massive increase in bank reserves is now part of the Fed’s “ample-reserves regime.” By maintaining more reserves than the banks need for protecting deposits, the Fed finds it easier to control interest rates.

But reserve balances are reduced as loans are repaid. Since most of the loans held by the Fed are treasury securities, as those securities expire, their debt is repaid, and reserve balances drop. The Fed needs to replenish these securities to maintain reserves at desired levels.

Despite its name, the Fed is not a part of the federal government. It is a bank consortium owned by all the banks that are part of the Federal Reserve system. As a business, it has, as liabilities, not just the bank reserves but other business-related costs.

Trust in our money is vital to a healthy economy. The financial community watches the balance sheet of the Fed very closely. The Fed must maintain a healthy balance sheet to keep the financial community assured that our money is safe. It is sometimes a balancing act to do this while also maintaining high reserve levels.

Destruction of Treasury Securities

Like any other debt instrument, the destruction of treasury securities requires repayment to eliminate them. When we discussed the creation of treasury securities, we only mentioned borrowing as a means of putting money into the TGA. There is another way: taxation.

It would seem like taxation is a simple process; the taxpayer just transfers money from their account to the government’s account. Remember, the government’s bank account is at the Fed. The TGA can only be changed by the Fed.

When you write a check or initiate a funds transfer to the government, your bank instructs the Fed to transfer money from your account to the government. Below, in this chapter, we will go into a little more detail about a more nuanced look at an even more complicated cycle to paying taxes, but for now, the simple version is that the Fed creates money equal to your tax payment and puts that in the TGA. Your bank’s reserve account is decreased by the amount of your payment. At your bank, your account is decreased by the same amount as your tax payment.

With tax money in the TGA, when a treasury security expires, the tax money repays the debt destroying both the money in the TGA and the treasury security being repaid. But money is fungible. That money in the TGA could just as easily come from issuing a new treasury security. If the new issues of treasury securities is greater than the rate of taxation, governments create a deficit.

Deficit spending in the U.S. is the primary cause of the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement. The government issued treasuries to pay off expiring treasuries rather than raising taxes to repay them.

While there are no theoretical limits to sovereign government borrowing, there are practical limits. This deficit spending cannot continue indefinitely. If the debt levels rise too fast or too high relative to the output of the economy, it may, conceivably, consume the output of the entire economy just to pay the interest on that debt. Keeping a pool of lenders is still required with government borrowing. Remember, any money relies on the confidence of society in its integrity.

In this cycle described above, note that the deduction from your bank account destroyed bank account money. If the government spends money back into the economy, that money is recreated by the bank into someone else’s account but if it is used to repay a treasury, that money and the treasury are both permanently destroyed.

There is another complication to paying taxes. Since the government, foolishly, keeps April 15th as Tax Day, as Tax Day approaches, money in the TGA would spike and bank reserves would plummet. To prevent this, the Treasury has special bank accounts (Treasury Tax and Loan accounts or TT&L accounts) that hold the money so that the money can be transferred out of reserves and into the TGA in a way that does not drastically distort reserve balances.

Circulation

Creation, destruction, ensconcement, and circulation of money create an intricate dance in our economy. Most of us are unaware of the amount of activity initiated by each economic transaction. This works seamlessly behind the scenes, involves different types of money, and different economic actors.

We are now going to look behind the scenes. Most of us are familiar with only a small number of transaction types. We spend wallet money, use our credit cards, pay digitally online or with a phone app, or some even still write checks. In this section you will learn about other whole classes of transactions that circulate and ensconce money.

Velocity of Money

The concept of velocity of money is important to economists in evaluations of how well an economy is functioning and to predict future economic activity. It measures the rate at which money is used in purchasing goods and services.

Velocity is defined as V = GDP / M where V is the number of times money circulates in the economy in one year, GDP is the Gross Domestic Product, a common measure of the output of an economy, and M is the supply of money.

This equation comes from an economics relationship called the “equation of exchange.” This equation, MV = PQ, expresses a calculation of GDP as PQ, a theoretical construction of the total quantity (theoretical items) of an economy’s output times the theoretical average price paid for those items.

So far, we’ve talked about money creation from three sources: bank creation, Fed creation, and treasury securities created by government borrowing. What money is included in M, the quantity of money? In the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED) velocity is defined as relative to M1 or M2. The velocity relative to MZM has been discontinued.

So, what are these different M designations? These designations differ from country to country, but we will describe the U.S. monetary descriptions. M0 is wallet money in circulation. It does not include wallet money held in banks or at the Fed. M1 is wallet money plus money in bank accounts. M2 is M1 plus money in small money market accounts. M3 is M2 plus money in large money market accounts. The Fed has stopped reporting M3 numbers officially but still have an unofficial tally drawn from outside sources. That compilation reports an amount so near M2 as to be useless.

The importance of M designations holds less luster than in the past. Some economists thought that inflation could be controlled by changing the interest rates based on the quantity of money rather than monitoring prices and employment levels. In the 1970s several attempts at controlling the money quantity to control the direction of the economy met with failures. Those failures are forcing a re-thinking of that theory. We will offer some suggestions on that topic in chapter 11.

The velocity of money peaked at 2.19 in 1997 and bottomed out at 1.13 in 2020. As the amount of money increases, the velocity goes down. The huge plunge in 2020 was likely due to economic inactivity because of the Covid-19 pandemic coupled with a huge spike in money creation.

Velocity measurements only involve money circulating in the part of the economy that produces our goods and services. Yet money penetrates other aspects of our economy. These pools of money support other money circulations most of us know nothing about.

To give you an idea of the scale of these unknown circulations, compare the GDP measurements which document production on the order of $28 trillion in transactions in the U.S. The total of all transactions in the U.S. is $7.6 quadrillion (1,000 trillion). Each of these other circulations drains money from the GDP generating circulations into pools which lubricate these other transactions. We will discuss these other circulations in more detail in chapter 7.

Other Money Circulations

Generally, economics studies what happens as countries trade goods and services within the country and between countries. As we saw in the U.S. example above, that activity involves only a rounding error in the total activity of a developed country’s economic activity.

Some of these circulations include transactions involving GDP activity while others are solely involved with money circulation not involving goods and services of the general economy. These other circulations blunt the usefulness of velocity of money calculations. Money moves in ways not measured by velocity.

Cashless Payment Systems

Gone are the days when you could write a check and race to the bank on payday to cover the check before it clears. Payment systems often clear within a day or less.

Credit cards are linked to bank accounts and read at merchants’ point of sale terminals. Newer terminals accept contactless Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) or Near Field Communications (NFC) transactions initiated by a credit card placed near the terminal. A phone running a phone app can also initiate these transactions. These apps, like Apple Pay, Google Pay, or Samsung Pay, also offer wallets that can be used in online payments for goods or services. Providing a credit card number or using an online platform like PayPal, Venmo, or Stripe allow online merchants to receive instantaneous payments. Many of these same methods can transfer money from person to person.

The merchant pays a fee for many of these services, but the convenience and speed compensate for these costs. The companies providing the services bear the burden of collecting from the customer rather than the merchant tracking them down and dunning them.

Some money transfers go directly from bank to bank. Wire transfers, Automated Clearing House (ACH) transfers, and debit card transactions all go directly from one bank to another.

As funds move from bank to bank, the movement of money from one bank’s reserve account to another bank’s reserve account still must be part of the circulation process. The role of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in this process is still to be determined. Their goal is to make the process even easier and faster. Some critics contend that the introduction of CBDCs has more sinister motivations.

Payment Systems and Service Providers

A major payment system is the ACH. This originated with a California clearing house organization that cooperated with other states’ clearing houses to form the National Automated Clearing House Association (Nacha) in 1974. Nacha owns and operates the ACH network through its member banks and customers.

The Fed ACH processes government and commercial settlements over the ACH network. Their operations handle about 60% of all ACH settlements. The Electronic Payments Network (EPN) operated by the ACH handles the rest of the ACH transactions and offers a competitive alternative to the Fed ACH.

The Clearing House operates another system, the Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS) for clearing payments between banks. It handles large volume traffic on the network. It handles about 95% of international transactions between banks.

The Fed offers another settlement service between financial institutions that have accounts with the Fed. This is the National Settlement Service (NSS). NSS can settle accounts between multiple private-sector parties simultaneously and provide final settlement.

The Fedwire Funds Service offers large-value time-critical payments. It focuses primarily on large financial institutions for same day settlement transfers. These are bilateral transfers compared to the multilateral transfers that can be done through NSS. These bilateral settlements are gross settlements which may require adjustments while the NSS transactions result in a final settlement.

Credit card payment networks allow the use of credit cards around the world. Credit card networks are operated by each individual credit card company. These settlement systems operate globally.

An important organization in money transfers does not move money. Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) is a global communications network that offers secure communications between international banks. Its communications protocol minimizes miscommunication in interbank transfers. It is so important to international banking that ejection from the SWIFT system is enough to enforce sanctions against individuals or countries.

SWIFT has gained a reputation as a tool for U.S. hegemony and projection of power. As a result, many countries are forming alternatives to SWIFT. So far, none of these alternatives have developed the reach that SWIFT enjoys. The U.S. misuse of this system may eventually spell its doom.

Messages through SWIFT lubricate the transfer of money through other networks. Without those SWIFT messages banks are reluctant to make the transfers. Transfers through other means may result in errors, loss of automation, damage to the reputation of the bank, or result in sanctions being imposed on those banks which avoid using SWIFT.

The above discussions describe the movement of money. The financial markets have depositories and corporations that store and move financial instruments outside of or in addition to the banking system. Just as the movement of money has become a computerized record change, so too, have many financial documents become computerized records.

Most people don’t know that the stocks they purchase don’t transfer ownership of the stock to them. What is provided to them is the right to use a pro rata share of stocks owned by Cede & Co. Another corporation, the Depository Trust Company (DTC), holds the stock certificates on behalf of Cede & Co.

This example highlights some of the intricacies of financial transactions. As we outline the entities involved in financial activities, we can see that much of the money circulation is divorced from the descriptions of the economy we find when studying economics. In our discussion of the velocity of money calculation, for example, there was no thought given to these movements of money in its calculation.

Central Securities Depositories

As mentioned above, DTC holds securities for the owner of those securities, Cede & Co. DTC is a subsidiary of Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC).

Another subsidiary of DTCC is National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) which is not a depositor but assists DTC in settling securities trades. It provides other financial services including “netting” transactions.

Since many of the transactions involve movements of money from different people but involve the same banks, movements of money can be minimized by consolidating several transactions into one movement of money which the bank can then allocate to its different customers. Many of the entities improve efficiency by incorporating these tactics. This process is “netting.”

Counterparties and Clearinghouses

In financial trades between unknown players, it helps to have someone trusted by both sides to act as an intermediary. Clearinghouses act to bring two counterparties together. These intermediaries act as guarantors of the trades. They settle the payments and report the results to regulatory agencies. They consolidate multiple payments to the same banks (“netting”) to increase efficiency and minimize costs.

Several subsidiaries of DTCC act as clearinghouses. Fixed Income Clearing Corporation’s Government Securities Division (FICC: GSD functions as a clearinghouse for government securities trades. FICC’s Mortgage-Backed Securities Division (MBSD) handles mortgage-backed securities settlements.

Another clearinghouse is part of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) group. CME operates several derivative exchanges and a subsidiary, CME Clearing, acts as a clearinghouse for trades through their exchanges.

LCH (formerly London Clearing House) handles 50% of worldwide interest rate swaps. Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. (ICE) operates 12 regulated exchanges, and its clearinghouse divisions operate in multiple countries. ICE clears a wide range of derivatives clearing including interest rate, equity index, agricultural, and energy derivatives.

Other Payment Systems and Instruments

Over the Counter (OTC) Foreign Exchange (FX) and Interest Rate (IR) derivatives go through less regulated exchanges and are traded directly between parties. Exchange Traded (XT) derivatives are standardized contracts that go through exchanges. These include futures and options contracts.

The Foreign Exchange (FX) markets determine the relative exchange rates between currencies. These markets operated even during the days of the gold standard. These traded products include Spot FX (immediate exchange of currencies), FX Forwards (Exchange in the future for a fixed rate), and FX Swaps (exchanging two currencies with the agreement to reverse the exchange at a future date.)

As the above discussion shows, GDP, the common measure of economic activity, is just a tiny part of the money circulation. In chapter 10 we will put numbers to this circulation and describe a superior method of taxation that will more easily allow the government to balance its budget.

Sequestration

Money is the fuel that powers the economic engine. Circulation is essential for this engine to operate. When money collects in pools, it is no longer circulating. Circulation that occurs outside of the production and consumption of economic goods essentially removes that money from the general economy. Some pooling is essential. Savings are a way of providing for the purchase of more expensive goods or for later investments. Savings can smooth money flows.

A functioning economy requires a certain amount of circulation to function. Any sequestered money that reduces the money needed for the economy to function creates a demand for replacing that money. That means additional borrowing and a higher debt load for the private sector. The money that circulates in financial circles was provided by the general public borrowing it into existence. Its removal from the economy adds to the debt burden.

The huge money circulation in the financial sector we described in the previous section involves sequestration of huge amounts of money to mitigate risks. These financial circulations don’t interact very much with the functioning of the economy that produces our goods and services.

Economists (and especially financiers) will argue that financial transactions move money from inefficient parts of production to new, potentially more efficient, parts of production. This explanation fails to address the extremely disproportionate size of the financial flows.

There are more efficient ways of providing funds for corporations that are efficient. The corporate bond markets provide money directly to corporations. Those businesses that are more profitable (ostensibly providing more of what the public wants to purchase) can raise more money than those that profit less.

The purchase of ownership does allow those who think the company is moving in the wrong direction (and have the money) to purchase more shares and influence the direction of the company, even to the point of dissolving the company and selling off its assets.

However, the vast amount of money circulating in financial circles has little to do with economic production. Financial markets provide wealthy casinos where players bet on (often very small) movements in economic factors to increase returns on their money. This comes at a cost to the economy that produces goods and services by requiring replacement of the money sequestered in those operations.